Do you prefer Doctor or Doctress?

Recently I learned about discussions in Poland around the most appropriate word and grammatical gender to use when referring to a woman by her job title. Turns out, Polish speakers have historically used masculine forms of nouns to refer to members of a profession of both sexes, rather than using an explicitly feminine (in the grammatical sense) version of the same noun, but in the 20th century that started changing, reflecting the reality of more women in professions, and signaling a sort grammatical gender parity. I haven’t seen much comment on this English, so I figured I’d write about it. I’ve always found this sort of thing interesting, and language change is on my mind after having read John McWhorter’s Words on the Move. In fact, this is in the spirit of many of the topics McWhorter covers on on the Lexicon Valley Podcast (a favorite of mine).

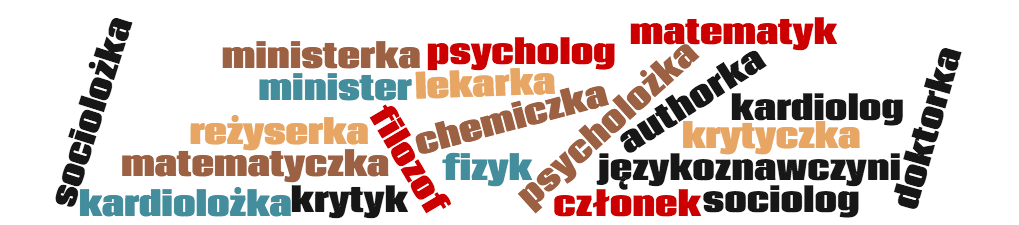

Consider a female medical specialist like a cardiologist. She might choose to refer to herself as a kardiolog (a masculine noun in Polish) or use the new coinage kardiolożka (a feminine noun) on her resume. Similarly, when you address her, she may prefer you use a masculine noun as part of the honorific construction, Pani doktor, or the feminine noun, Pani doktorka. An academic, say a female sociologist, faces the same dilemma: she needs to choose between socjolog and the less common socjolożka. Women in business and politics (think director, manager, president, prime minister) also have a decision to make. In the public sphere, businesses, newspapers and government offices must decide how to refer to women in these positions, and those decisions have cultural and political implications.

As part of an interview 2015, Professor Jan Miodek, a Polish linguist, language maven, and a sort of unofficial authority on proper language, touched on the issue in an article on dzennik.pl:

In the 1970’s, we [started using feminine versions of nouns]: dyrektorka (business director), tłumaczka (translator), reżyserka (movie director), and reporterka (reporter). Then came [the usage of the feminine honorific followed by a masculine noun]: dyrektor, reżyser, tłumacz (translator), and reporter. In the case of these senior roles in business, the masculine form somehow conveys a more serious impression.

On the other hand, he goes on to say that for title of minister (as in “minister of defense"), the masculine form feels unnatural to him, and that ministerka (feminine) sounds more natural. He notes that using ministerka is consistent with trends in other languages: the Czech noun ministryně (feminine, from ministr) is in common usage, as is the German feminine noun for chancellor Kanzlerin (from Kanzler).

Who gets to decide?

Of course, there’s no objectively “right” answer to usage questions like these. They reflect the feelings of members of a language community, and the particular trajectory the language and the culture have taken. Questions of usage touch on feelings about identity, and depend on both the historical baggage carried by words, and the structure of the language itself. Something like consensus may eventually emerge, but in the meantime the best thing we can do is let people decide for themselves how they want to be referred to, and advocate for that.

In [another article] (http://www.gazetawroclawska.pl/artykul/311691,jan-miodek-socjolozka-czy-pani-socjolog,id,t.html), Miodek references the large variation in forms still in play, citing the choices made in just one article in Gazeta Wyborcza, a major Polish language newspaper. The list of nouns included: psycholog kliniczny (clinical psychologist, masculine), wiceprezes (vice president, masculine), publicystka (publicist, feminine version of publicysta), socjolożka (sociologist, feminine version of sociolog), autorka (author, feminine version of autor), adiunkt (adjunct, masculine), członkini (member, feminine version of członek), krytyczka literacka (literary critic, feminine version of krytyk), and filozof (philosopher, masculine), among others.

I also found an interview with Katarzyna Kłosińska, another Polish linguist. She was also asked whether people should be using the feminine forms of nouns for professions, and makes a point about personal choice:

Of course, we can do it [use feminine versions of the nouns], but the language does not absolve of us responsibility for those choices. If we’re not careful they may have the opposite [from the intended] effect. All language processes should happen naturally. If in a newspaper we read about “critics” (here, she uses the feminine form of krytyk, krytyczka) or “psychologists” (likewise, the feminine psycholożka), then over time we become familiar with such forms. [To the degree that I] encourage the use of female forms, it’s for purely functional reasons. It is easier to say “the physicist” (fizyk, masculine) fell in love with a chemist (chemiczka, feminine)" than “the physicist fell in love with a chemist (chemik, masculine)”, because this second version sounds strange, although it is correct linguistically. However, there are many women who do not accept female forms, they want to be called “president” (prezydent, masculine) “lawyer” (adwokat, masculine) or “doctor” (doktor), and this is also natural and understandable.

She goes on to say that she personally wants to be referred to using the traditional, masculine noun for linguist, językoznawca (a noun, which, although it ends in “a” and takes ending like a feminine noun is itself masculine), rather than an explicitly feminine form like językoznawczyni.

Despite a lack of consensus, newspapers and government organizations will naturally want to standardize in the interest of consistency of style, and respect for changing norms. In fact, I found a government report from 1995 that was a summary of “expert” opinion on the consensus on titles.

How does feminine noun formation work in Polish?

The grammar and sound system of Polish define a set of alternatives for forming feminine versions of masculine nouns:

-

Simply adding “ka” to the end (by far the most common). For example: doktorka, lekarka and ministerka.

-

Adding “ka” after an additional syllable, or a consonant change. For example, krytyczka (critic), and kardiolożka (cardiologist).

-

Adding a feminine suffix other than “ka”. For example, członkini (member) is an example of a feminine noun derived from członek.

The choice of an alternative is subject to some practical constraints. The natural feminine version of a noun may already have another meaning. For example, in Polish, the masculine noun for critic is krytyk, which would make the natural feminine form krytyka. Unfortunately, that word is already taken: it means “criticism”. An analogous situation exists with matematyk, mathematician, where matematyka already means “mathematics”. The feminine noun for professor, profesorka is also perceived as unavailable by many speakers, not because it means something competely different, but because it has a decidely informal tone.

Alternatively, a particular rule might lead to a word that’s difficult to pronounce, or unnatural for Polish. For example, the word adiunkt would become adiunktka, creating an awkward consonant combination “ktk”, hence the use of krytyczka. Likewise, the ż in the formation the feminine version of kardkiolog avoids a the consonant cluster “gk”, which is quite difficult to pronounce without adding a stop in between the two hard consonant sounds, or changing the sound. In Polish, we see a common pattern of “softening” the “g” sound to “ż” (similar to the “z” sound in the French word “azure”).

A few observations about grammatical gender

Polish has three grammatical genders for nouns: masculine, feminine, and third neuter gender. Every noun has a grammatical gender. In Polish, you can usally determine the gender of a word just by looking at its ending in the nominative form (i.e., the form you’ll find it in a dictionary that’s used when a noun is the subject of a sentence). For our purposes, it’s enough to know that feminine nouns usually end in “a”, and it’s normal to use a feminine noun when referring to a female person. For example, kobieta (woman), żona (wife), dziewczyna (girl), córka (daughter) and siostra (sister) are all feminine, and mąż (husband), chłopiec (boy), syn (son), and brat (brother) are masculine. Those nouns, like all nouns, take on different endings depending on how they’re used a sentence.

Every noun, whether it refers to a person, an animal or an inanimate object has a gender. For reasons mostly lost to history, it so happens that word wiewiórka (squirrel) is feminine, stół (table) is masculine, and krzesło (chair) is neuter.

The details of the rules aren’t important. But what’s critical is that we not to confuse this idea of grammatical gender with biological sex or any other cultural notion of a gender. No Polish speaker will tell you that there’s anything particularly feminine about a lamp, that a table is male, or ever be confused about the existence of male squirrels. And when a linguist talks about gender they’re just talking about the pattern of variations in pronunciation and spelling that are part of speaking Polish grammatically.

How grammatical gender can influence meaning

While it’s true that grammatical gender is a technical concept without reference to biology, there’s still some evidence that the gender of a word can color perceptions.

In Polish, women’s names almost exclusively end in “a", and speakers will tell you that names like “Yvonne”, “Heather”, or “Lauren” all sound a bit off because they end in consonants. It’s common for languages to have implicit rules for the spelling and pronunciation of male and female names, and we all have the experience of enountering a name that doesn’t follow gender rules we’re used to seeing.

Many Polish speakers will tell you that gender influences how they might anthropomorphize an animal: a wiewiórka (squirrel) feels feminine because of that “a” ending, and the fact that grammatically speaking it will behave just like a word like kobieta (woman). Or perhaps, it’s the similarity to a female name that (think Pani Wiewiórka") implies a biological sex. Likewise, because the word myszka (mouse) is feminine, Polish children may do a double take when they’re introduced to Myszka Mickey (Mickey Mouse in Polish).

It’s worth observing that a neuter noun will never be used to refer to an adult person. In Polish, unlike some other languages with grammatical gender, neuter strongly connotes sexlessness, or in the case of words like dziecko (child), a child who hasn’t yet undergone puberty. This shouldn’t be confused with generic, sexless nouns–the equivalents “human” or “person”. In fact, while the word for human is człowiek, a masculine noun, the most common word for person is osoba, which is a feminine.

Can we relate this to English?

Of course, English doesn’t have grammatical gender, but we do have words for professions and titles that come in male and female versions. When I thought about how I might draw an analogy to English, what leapt to mind immediately were the considerations an English speaker would’ve brought to mind when thinking about similar questions Americans have asked in the past around historically “gendered” professions:

-

Should it be “flight attendant” for everybody, or should we use “steward” for men, and “stewardess" for women? How determinative is the gendered ending “-ess” and the baggage it has? Should we say waitor and waitress, or use the neutral word “server”?

-

Why, at one time, did some English speakers feel a need to say “male nurse” explicitly when men started joining the ranks of the nursing profession in larger numbers.

I posit that for most English speakers “flight attendant” has a more professional connotation than stewardess. In that way, it’s perceived in a similar way as profesor and językoznawca by many Polish speakers. However, for many other titles, Polish speakers are beginning to feel that the feminine versions are more modern and inclusive.

Polish has a feminine noun for nurse, pielęgniarka, and the word, as an in earlier time in English, specifically refers to a female person in a particular role as a medical professional. Here, there’s a clear parallel to English. It’s not the grammatical gender that’s important, but the meaning. The gender is clearly a consequence of that meaning. Grammatically speaking, like the word osoba, there’s no reason that you couldn’t use pielęgniarka to describe male and female nurses, but because of the history, that won’t seem quite right to some speakers.

The perils of judging as a non-native speaker

I found myself asking whether the Polish feminine noun endings have accumulated baggage like the “ess” ending in stewardess: a suggestion of diminutiveness or less-ness. There’s some academic work suggesting how attitudes are embedded in language like this. When I sat down to write this my intuition was that the feminine endings did connote diminutiveness.

I’ll unpack that a little. Polish has a rich grammar for taking an existing noun and creating new dear, small or cute versions of that noun. This is done by appending one more diminuitive suffixes. Diminutive ersions of feminine nouns often end in that same “ka” that’s used to feminize a masculine noun, for example, herbatka (“a bit of tea”), or krówka (calf, literally a little cow, from krowa, cow). For masculine nouns, we also see the consonant k in the diminutive suffix “ek”, for example, chlebek (“a small loaf of bread), ciasteczko (a cookie, literally a little cake, from ciasto), and piesek (a little dog, from pies).

When I see Polish words ending in “ka”—diminutive or not—I can’t help seeing them all as connoting smallness or cuteness, as a sort of surface feature of the word that points to something deeper about its meaning. That is decidedly not how a Polish person will see those endings. Most of the time, those endings are experienced as just part of the syntactic machinery of the language, and just because the “ka” may be used to express diminutiveness in some context, a speaker won’t report any sort of misogynistic or patronizing flavor to that ending when interpreting a familiar word. My experience is not so different from the reaction of the 12-year old American kid studying German when he or she sees the word Ausfahrt (“exit”) and hears “fart”. I’m still amused when I think about the first time I saw pij mleko on a billboard (that means “drink milk”, where pij, drink, is pronounced like “pee” in English).

Wrapping up

Despite my status as a Polish language outsider, and the difficulty in generalizing from quotes and anecdotes from native speakers, I feel comfortable drawing a few conclusions. First, forces at work within the heads of Polish speakers that really count are not fundamentally different from those of English speakers. The question hinges on changing ideas about identity, and evolving social norms. The language establishes a set of rules governing alternatives that are in play, but in the end it’s the meaning of words that count. Second, grammatical gender does create more opportunities for dissonances between historical usages of words and new uses, and colors perceptions in some subtle ways. In that sense, Polish speakers are going to be harder pressed to find professional nouns that sound neutral in the same way that “flight attendant” does. Finally, this is just another example of how language is undergoing constant change, and in the end the only authority on meaning is the language community itself. To quote John McWhorter from “Words on the Move”:

One of hardest notions for a human being to shake is that a language is something that is, when it is actually something always becoming. They tell you a word is a thing, when it’s actually something going on.